|

|

|

SLIDE SUMMARY: Necrotizing fasciitis is characterized by

pannicular and fascial necrosis.

However, it can be caused by a variety of infectious agents, and each

syndrome has some distinctive pathological and therapeutic features. If not otherwise specified, “necrotizing

fasciitis” tends to imply that due to streptococcus. Surgical treatment by complete excision and

drainage is mandatory. Later

reconstruction depends on principles related to large wounds of any cause.

|

|

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

|

|

|

Numerous papers and

book chapters exist to educate you on the basic biology and clinical science

behind these infections. This

presentation will focus on the clinical arts of managing these problems for

good results: for acute life-saving treatment and for long term

function-restoring management.

|

|

|

|

Necrotizing

fasciitis can mean any of several forms of severe, rapidly progressive and

lethal (if untreated) infections. Much

of the drama and public attention to “necrotizing fasciitis” goes to classic

Group A streptococcal panniculitis.

The terminology is not important.

Understanding the behavior of these infections, is important: the

generic implications for life and death and urgent thorough treatment, but

also the relative differences and nuances of care that arise from the types

of organisms that are responsible.

|

|

|

|

All necrotizing

fasciitides have in common that the infection causes infarction and

destruction of tissue, far in excess of the normal injury that occurs from

reactive inflammation. As with most

inflammatory soft tissue pathologies, the primary target or susceptible

tissues are the subcutaneous adipose fascias.

Rapid extension of the disease, tangentially through the fascias, is

the norm. Skin necrosis is typically a

secondary event, due to loss of the trans-pannicular perforators which

provide blood supply to the skin, or due to toxic chemical injury from the

organism (depending on the type of infection). Muscular fascias are likewise more

resistant, and muscles underneath, or viscera, can be involved by extension

(or they can be a primary target for Clostridia).

|

|

|

|

When the disease is

active and rapidly spreading, gross pathology can be divided into several

zones which have implications for surgical treatment (see Slide 7).

|

|

|

|

General classes of

rapidly progressive infectious panniculitis, or toxic necrotizing fasciitis

include these:

|

|

|

|

Synergistic

gangrene: This is the most common type

in daily medical practice. It is

usually due to a mixed flora of pyogenic enteric organisms, typically aerobes

and anaerobes, which create synergistic microenvironments which facilitate

each others growth and metabolism.

Being due to enteric flora, these infections are most prevalent in

abdominal and pelvic related problems, including bowel perforations,

complicated genitourinary infections, enteric contamination of skin and

musculoskeletal laceration or ulceration, perianal or perirectal abscesses,

and so on - including the classic Fournier’s gangrene. Pathologically, there is progressive

suppuration and abscess formation in the adipose panniculus, working its way

into various fascial planes, and sometimes killing muscle. Patients can be extremely ill from general

inflammatory effects and from endotoxins and others toxins. These patients can be gravely ill, and

prompt drainage and debridement are mandatory. However, the biology of these infections

are distinctly different than the “necrotizing fasciitis” of streptococcal

infamy. These infections are due to

organisms which are individually fairly benign, the stuff of everyday GI and

GU infections. It is in the synergy of

mixed flora that they become more destructive. There is a bit of latitude in the surgical

treatment: there is no lesser sense of

urgency, and delays in care ARE NOT excusable, and thorough debridement

remains the goal - BUT - if the exigencies of the illness and logistics of a

trip to the OR are hampered in any way, these patients have a bit more leeway

for a simpler drainage and debridement.

For example, if the problem occurred in the groin after a vascular

procedure, and the patient is on potent anti-platelet drugs, these abscesses

can be effectively managed by gross debridement of loose necrosis and pus,

and wide opening of the wound, but without incurring the bleeding of a formal

sharp excision through still viable but highly inflamed and hyperemic

tissues. This will generally arrest

progress of the infection, while maintaining a good risk-benefit balance for

the patient. Broad spectrum

antibiotics are obviously mandatory.

|

|

|

|

Clostridial

myofasciitis - Aka “gas gangrene”, is often the result of ranch and soil

injuries, or enteric injuries. This is

a serious fulminant disease which requires a serious expedited surgical

response. Muscles as well as fascias

are targets. Exotoxins have lytic

necrotizing effects on the infected tissues, but they also have disseminated

intercurrent toxicities for other organs.

No delays in management can be tolerated.

|

|

|

|

Streptococcal

fasciitis. This is what people really

mean when they talk about the classic N.F.

Strep species other than in Group A, and staphylococcal species can

all cause the same syndrome.

Incidental other organisms can cause the same thing, including

unexpected oddballs such as salmonella.

However, it is the exotoxins in Group A strep which are particularly

pernicious and prone to rapid spreading and “streptococcal toxic shock

syndrome” (STSS) with intercurrent organ failure. It can start off a bit more insidiously

than some of the other types of fasciitis, but when the diagnosis is made,

the imperative for rapid surgery is the same as for gas gangrene. These types of fasciitis can have

distinctive findings, including:

non-odorous (as opposed to synergistic or enteric gangrene); fascial

necrosis and suppuration are often not lytic and cavitary (as is the case for

enteric abscesses); severe watery edema, which is a survival and

proliferative advantage for the organisms;

scarlet color. Complete

thorough excision is required. See

Slide 7 for more details.

|

|

|

|

Atypical

infections. These are due to fungus,

mycobacteria, actinomycetes, and such atypical non-bacterial pathogens. They tend to be “slow” infections - think

TB versus pneumonia or a post-pneumonic abscess - but once vessels start to

occlude and tissues infarct, the destruction can seem to occur quickly. Typically, a relatively slow granulomatous

inflammation was cooking in the fascias prior to severe skin

involvement. Mucormycosis is

distinctive in that vascular occlusion rather than inflammation or

exotoxicity is the cause of problems.

These patients typically have a more insidious and seemingly less

urgent onset, but the implications for curative surgery and reconstruction

are the same.

|

|

|

|

As discussed in

later slides, surgical excision is mandatory, and the sooner the better, with

Clostridial and Streptococcal N.F. having the most immediacy for

surgery. However, the nature of the

required surgery is the same for all such patients with any of these

diseases. Surgery is required for

three components of the problem:

|

|

1 - GET RID OF THE

DISEASE, by as thorough and complete wound excision or debridement as

possible.

|

|

2 - PATCH UP THE

RESULTING WOUNDS, by the the usual arts of plastic surgery, whenever wound

conditions and patient conditions permit.

|

|

3 - RECONSTRUCT LATE

SEQUELAE such as scar contractures, or amputation management, etc.

|

|

|

|

The surgery is

analogous to the surgery needed for burns, deglovings, and any large or acute

wound. Burns and trauma do not have

the same type of illness, and acute and critical patient management are

different than N.F. in many ways. But,

the surgery of cleaning up the mess, preparing the wounds for closure, then

patching them up, then restoring function - that is what core plastic surgery

is all about. Large wounds, small

wounds - it doesn’t make a difference - the surgical principles and methods

arte the same for all of these conditions.

|

|

|

|

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

|

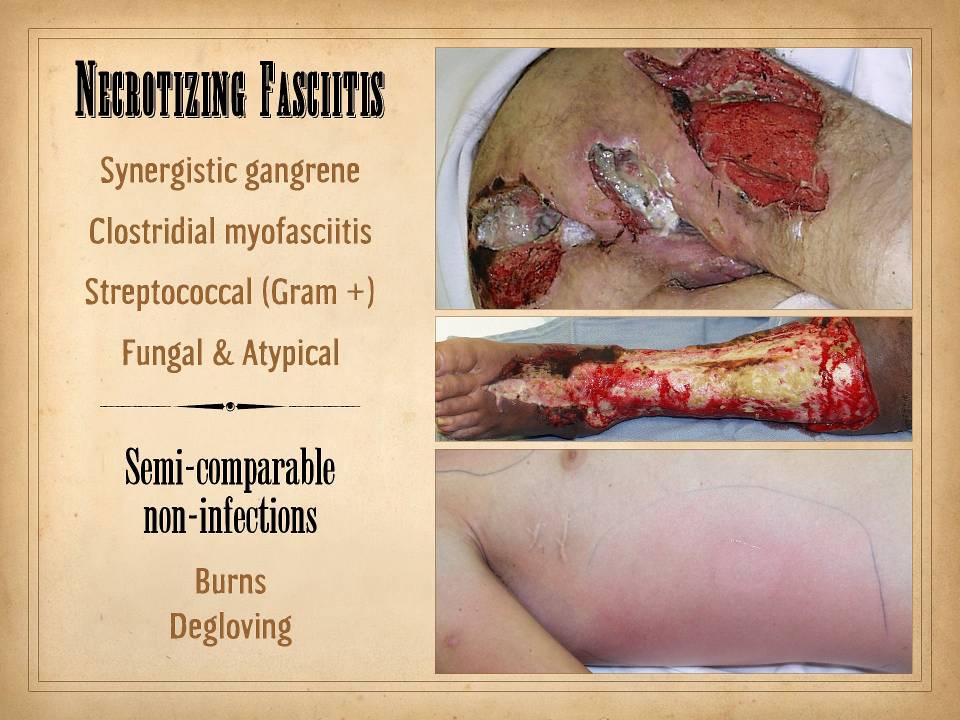

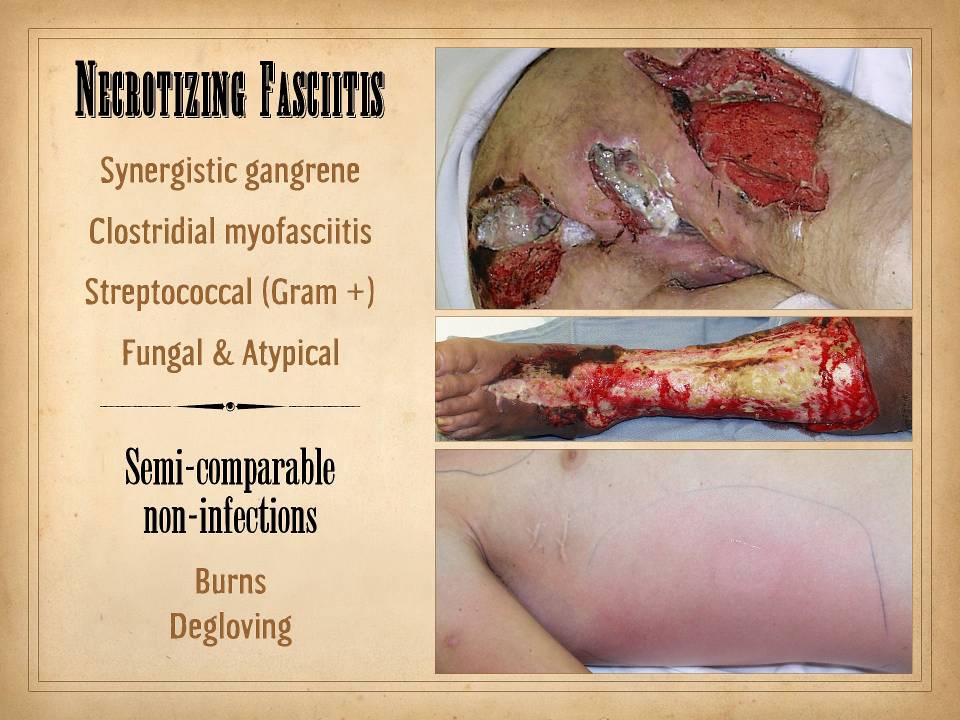

TOP - A young

derelict paraplegic patient with long standing pressure sores. Synergistic fasciitis - Fournier’s gangrene

- is a very infrequent complication of ordinary ischial pressure ulcers, and

in fact, it was not the problem here.

Rather the patient developed pressure necrosis of the anus, leading to

ischiorectal infection, which then spread rapidly, involving tissues

throughout the buttock, pelvis, and thigh, including other pressure

bursas. The image here is a couple of

weeks after debridement and wound care, ready to begin closure.

|

|

|

|

CENTER - A patient

with severe rheumatoid and multi-drug immunosuppression developed fairly

rapid skin necrosis, leg ulceration, and febrile toxicity. While rheumatoid panniculitis notoriously

causes extensive ulceration of the leg, that process is relatively slow and

indolent, and does not involve the muscular proximal leg. Biopsies and cultures showed aspergillus.

|

|

|

|

BOTTOM - This is a

19 year old man who developed fevers and malaise after a minor skin

scrape. This was followed by rapid

erythroderma, edema, pain, and progressive toxicity. This is the quintessential Group A Strep

N.F.

|

|

|

|

|